“Wisdom sits in places. It’s like water and never dries up. You need to drink water to stay alive, don’t you? Well, you also need to drink from places. You must remember everything about them. You must learn their names. You must remember what happened at them long ago. You must think about it and keep on thinking about it. Then your mind will become smoother and smoother. Then you will see danger before it happens.”

Cave-like overhang at ~4,700 ft above sea level and the object of our expedition.

- 2015 -

First, the good: We began cataloguing local flora/fauna (and geological formations) with a 10 mile hike centered on the exploration of a cave-like overhang, located at approximately 4,700 feet up the side of Unnamed Mesa.

Wildlife sightings were constant, and - although we finished the hike dog-tired - we considered the day's expedition a success. It was only upon returning to the property later that evening, after a nap near Conchas Lake, that things began to turn against us...

Eight-foot, tree-climbing Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum), photographed atop Unnamed Mesa.

When you're 50 miles from the nearest medical facility, clustering illusions ("bad news comes in threes") sometimes appear more than psychologically grounded. In this case, it was a trio of near misses that spurred fanciful conjecture of the most preposterous sort.

We encountered our first threat during a routine trek from the nearest vehicle parking - off Magnolia, ~30 miles from Tucumcari - through an overgrowth of Cane Cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata), Desert Spoon (asylirion wheeler), and Desert Prickly Pear (Opuntia phaeacantha). It was the Prickly Pear (sweet, but seedy) that sheltered our attacker.

"Let's skirt this patch," I suggested, and proceeded to hook to the right of a ~6ft diameter, ankle-high growth of the fruity cactus. My cousin, noted pharmacological technician Sam Bender, retreated abruptly just as we cleared the patch.

"Oh Shit!" - a near scream and altogether natural response accompanied my cousin's flight off the game trail.

The first thing I perceived was the rattle - much louder than one might imagine, due, perhaps, to the relative size of the creature. Next, I saw it - a Western Diamondback Rattler (Crotalus atrox) - reared up hip-high and still rising from the edge of the cactus patch. The serpent was easily six feet long and as thick at its center as your biceps.

It glared at us menacingly, less than a yard from where we first stood, ready to inject upwards of 800mg of hemotoxic venom, which - if left untreated - results in death 10-20% of the time.

A similarly sized Western Diamondback Rattler (Crotalus atrox), encountered and photographed as we approached the property the day before.

We both moved quickly at that point, turning and running diagonally in opposite directions away from the rattler. The quickness of that retreat, coupled with that notably aggressive species' to readiness strike, took me straight into the nearest Cane Cholla.

The trip back to camp was mostly uneventful, although I limped slightly due to the dozen or so barbed spines embedded in my thigh just above the knee, and the tendency for my denim pants to rub against that wound made for an unpleasant quarter mile. But our adrenaline levels were understandably high at that point and we felt well-nigh invincible. A belt of bourbon later and I was down to my skivvies, tackling the Cholla spines one-by-one with the pliers on my trusty Leatherman. Surely the worst was over.

A Cane Cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata) of the sort embedded in my thigh following our hasty retreat from the Diamondback rattler.

We had thought our adventure complete for the night but a massive (un-forecast) cumulo-stratus thunderhead approached from the northeast shortly thereafter. 60mph straight-line gusts encouraged gulps of 100 proof spirits, and, while I wouldn't recommend drinking in a survival situation, our tent was tied down, reinforced, and there was a darkening field of aggressive rattlesnakes between us and our only means of escape.

The rain hit hard, as did the lightning, while accompanying thunder reverberated continuously off 360 degrees of Mesa. The sound approximated war-drums and those deep, bellowed chants encouraged our fear of the storm's electro-magnetic potential. Moreover, the downpour that eventually followed the gale-force gusts was so unfamiliar to the rocky top of our "mini-mesa" that much of the deluge bounced off the ground and back into the tent, effectively circumventing the rain flap.

Rain and darkness in the distance.

We awoke damp, slightly hungover, and enormously relieved. Quickly, we packed and headed back across the dreaded Cholla field, sticking as much as possible to the game trails that enmesh the area. Fully packed, then, we discussed the prospect of sugary drinks and ice in our water and protein in our diet.

You see, at that point, nearly 24 hours had passed since anything but trail mix and whiskey (and water) were consumed. That fact may first appear silly, negligent even, but we had more food in our possession and simply anticipated a timely arrival at environs with broader culinary options. As it happens, our departure was not imminent.

Garita Creek was now flowing rapidly over the only graded road between us and civilization, and, while the silty water was only waist-deep, the clay mud threatened our humble city vehicle with temporary custody, during which the next summer storm would undoubtedly build up and wash us away along our remaining supplies.

Fording the flooded creek simply wouldn't do, so we took a couple bites of trail mix and set off for help - three miles away, where the nearest neighbor was dug in to the high desert.

Garita Creek crossing, where flash-flooding temporarily stranded us.

Our last hope, short of hitchhiking back to Tucumcari for a tow, were Bill and Marge, permanent residents of the area, and generous owners of a two-ton truck that would eventually dragged our vehicle across the flash-flooded, high-desert creek crossing. We promised beer and steaks upon our return, arranged to enlist their water dowsing services when the time came to dig a well on Porcupine Ranch, and hit the paved state highway five miles later.

In six hours were were back in Norman, and ice came easily from the fridge door, and beer was wonderfully cold, and the spider in the bathroom seemed innocuous rather than threatening. Did I mention we've already already laid out plans for our next expedition? Several cabins dot the valley between the Variadero and Unnamed Mesa, all built (with much labor, no doubt) from unfinished local stone. Artifacts dot the ground surrounding these early 20th century homesteads and the story of their inhabitants demands to be told.

Stone ruins of former settlers (center right) - to be explored in subsequent expeditions.

- 2016 -

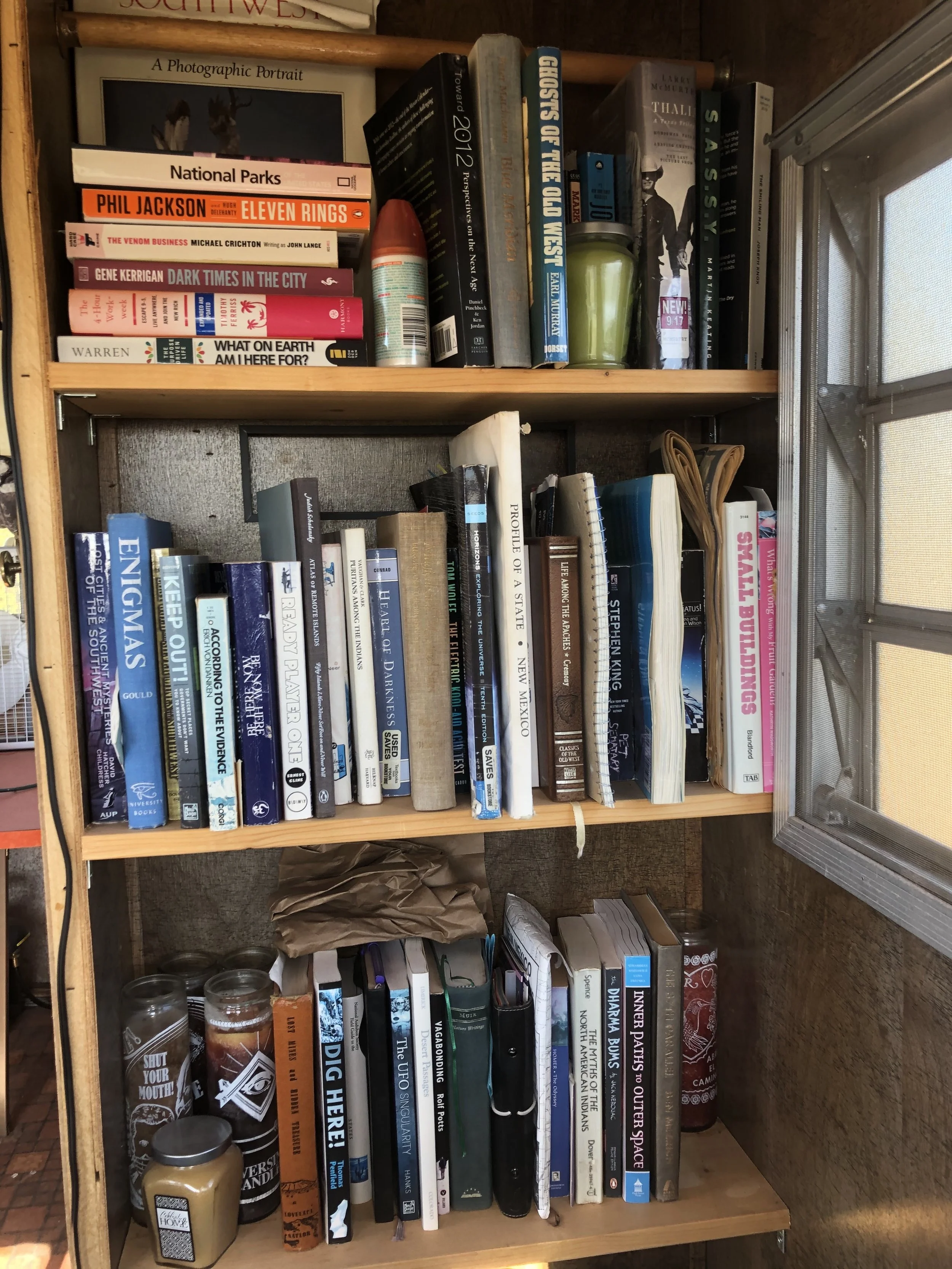

In Garita, folklore shapes perception just as readily as more established western religions implicitly shape the daily life in the city. Take the issue of water. As the Chihuahua desert creeps north, the average rainfall will continue to decline from an already low ~20 inches annually, and life - already difficult when sheepherder's abandoned their stone cabins to fight in WWII - will be harder to sustain. So, local practices like water dowsing will undoubtedly proliferate rather than die out. Where LTE doesn't reach, the sorts of seers and charlatans that characterized the Burned-Over District command more influence than Google-scholar, and - sometimes - their methods work.

A sheepherder's stone cabin.

But first, we did reach that stone cabin in the distance , and - perhaps more importantly - we've 3D scanned it for remote analysis. Using a series of high definition still images and a piece of Autodesk software now known as Remake, a surface mesh (with texual imagery superimposed) is now accessible to the general public, in virtual reality, at University of Oklahoma Libraries. Importantly, we can also take measurements, after the fact, by re-engaging with extremely detailed 3D models that no longer hide rattlesnakes. With ongoing evolution of low-cost drone equipment, and photogrammetric processing software, the entire Garita Valley can be surveyed and 3D mapped for virtual exploration from anywhere and with anyone.

Excavating a half-mile driveway.

Also, we built a winding, half-mile long driveway, Essentially reclaiming a forgotten public easement that only ever existed on a (decidedly low-tech) 70's era surveyor's map. At that time, the nearby Concahs Dam - designed and built by the U.S. Army Core of Engineers - was still a going concern, and the resulting lake was supposed to support a community of "ranchos" that never materialized. Vehicle access allowed the property to function as a staging ground for an ambitious ascent of Variadero Mesa, whose red-hued battlements are sheer. From atop the mesa, you can see the extreme Southwest fingers of the 25 mile long lake.

Atop Variadero Mesa, observing a conical stone formation to the Northeast.

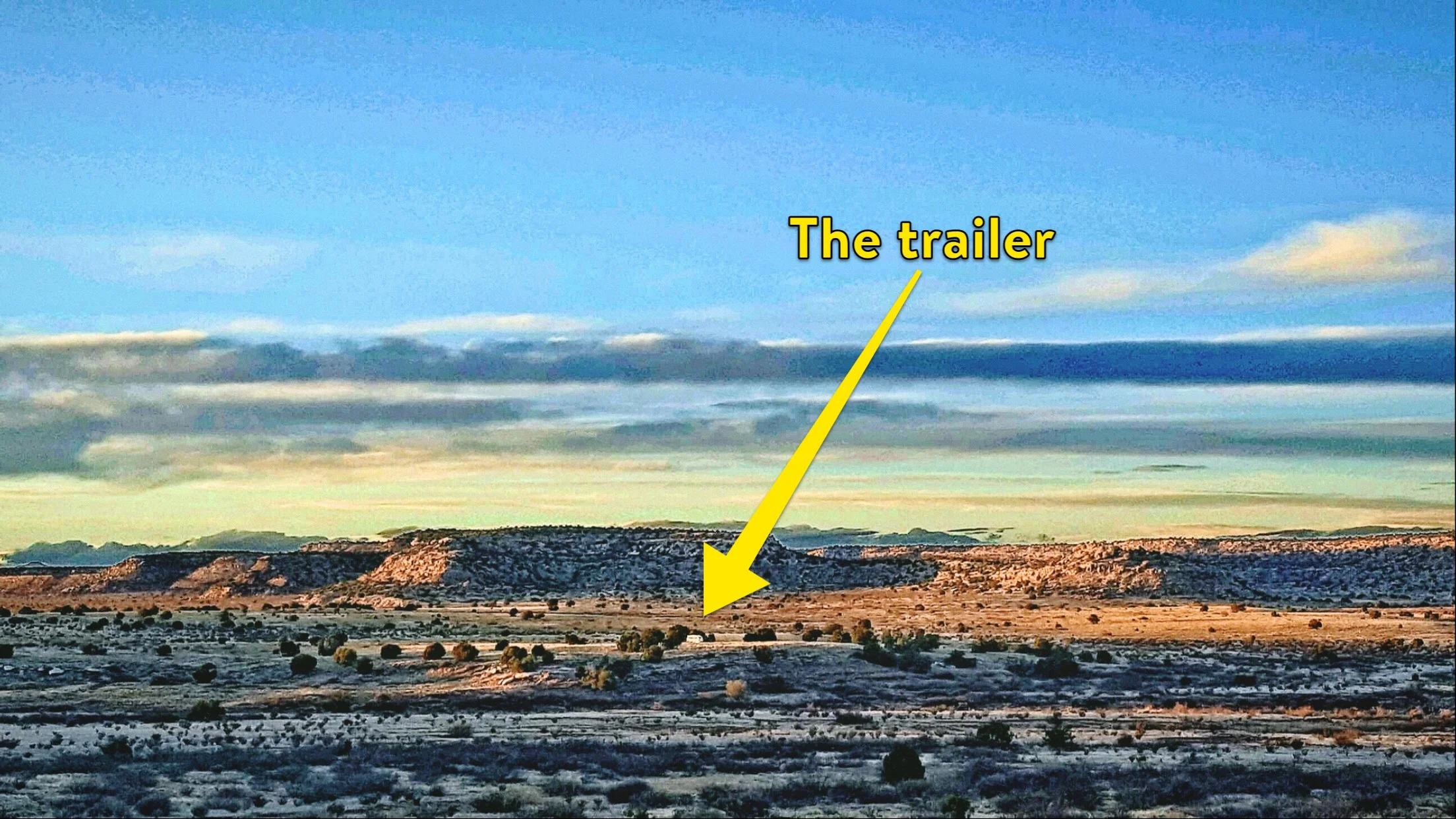

We completed the year with the installation of the first permanent shelter on the property, a "canned ham" travel trailer, complete with brown and orange racing stripes. Once in place, we were able to comfortably wait out the late-December cold. But there, tucked into our 20-degree-rated Marmot mummy bags, dreams of 100 roving tornados - encircling the trailer and stretching out across the Garita valley in every direction - haunted us. The next day a massive storm system swept in from the Northwest and shook the stilted trailer all night long. Next project?: A viewing deck above the trailer.

Our home on the property.

-2017-

Dusk in the Garita valley.

Solar power, a full-sized bed (under roof), a fire-pit seating/cooking area, and a navigable road to the front door - These are some of the recent additions to the property that have made visiting Porcupine Ranch a relatively comfortable experience. (Water is still and issue, but, at an estimated ~$10,000 to hit the water table, we may be trucking in drinking/washing/cleaning water for some time to come). These "upgrades" have also brought into question our reasons for being out there, far from home.

The property was never about creature comforts, or fully recreating the at-home living experience in a place far away (e.g. pure escapism). I have to constantly remind myself (and our guests) that Porcupine Ranch mission "success" is defined by the briefest moments of purest contentment achieved just before sunset, or at dawn, when one removes blankets or boots from blistered feet and stares out across the dry Garita creek bed towards the exposed sandstone in the distance, climbing 300 feet up the side of unnamed Mesa. Pinks in the morning, deep reds and purples in the morning.

Silva Gang hideout - San Miguel County, New Mexico.

Pinks in the morning, deep reds and purples in the evening. That's why we are here, right? To experience the color and the light and the shadowy contours lacking both that define - or begin to hint at - the New Mexican experience that has drawn traders and mystics and outlaws . Outlaws like Vicente Silva who was seen as a Robin Hood-type character by the Garita locals in his day, some of which still own property in the Mesalands between Tucumcari and Las Vegas, bordering the Canadian River. Did the Silva gang slow down to watch the sunset - did they emerge from their cave hideout at dawn to see the sun breach the top of the mesalands?

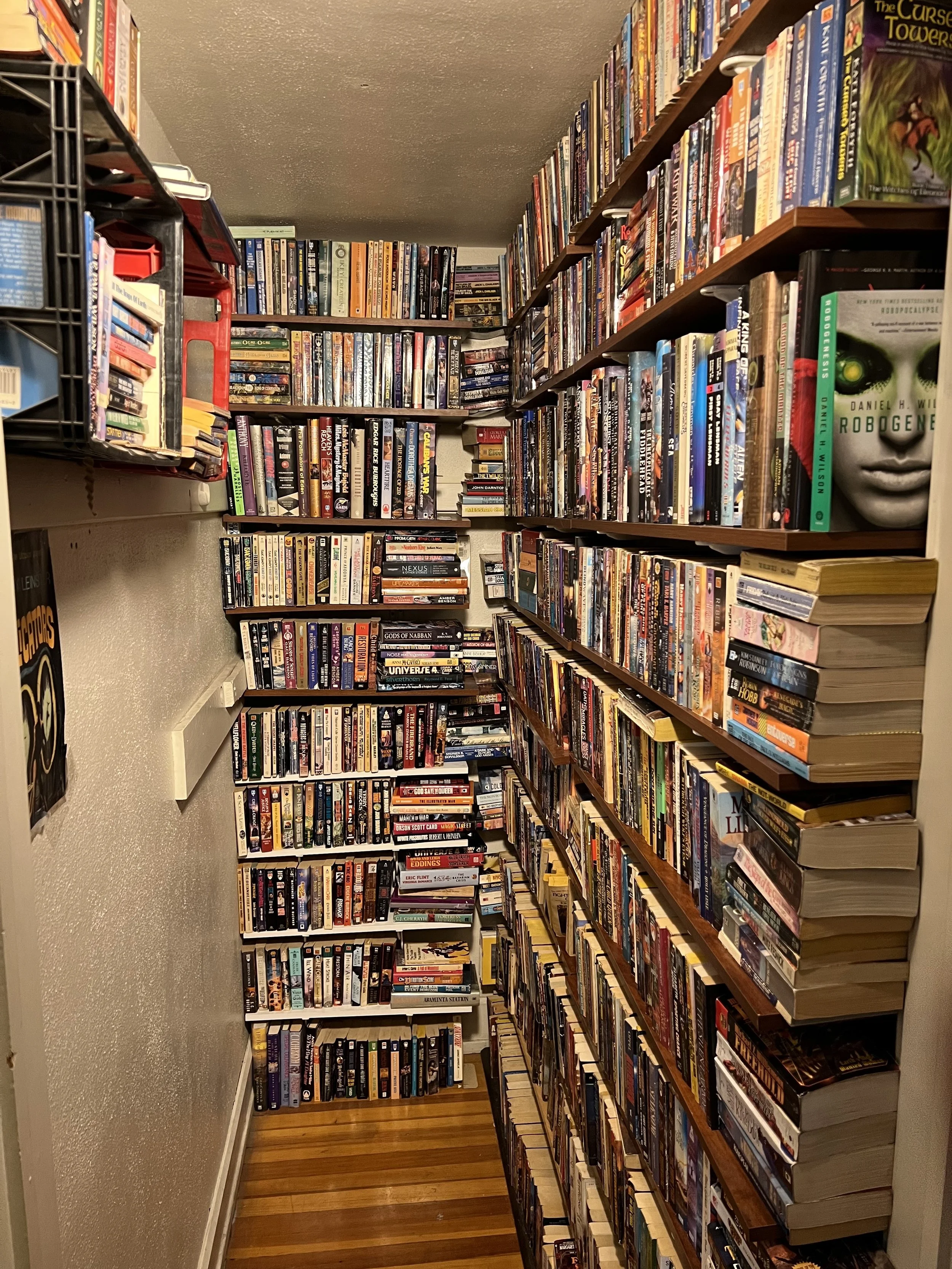

Light to read by and an old box fan to move the air during the heat of the 100+ degree summer days. That's not enough to be considered feature creep, surely. A cabin would be nice though, and an AC window unit, and maybe a stereo or electric guitar amp. But then the property would begin resembling the Conchas Lake State Park campsites, across the lake, where RV generators run all night, drowning out the owls, and the glow of sattelite tv sets diffuses through blackout blinds and drowns out the stars.

-2018-

Pecos National Historic Park

I had the good fortune of visiting NM four times in 2018. Off the property, we hiked the Mora pass and the shore of the Rio Grande near Santa fa while, on the property, we constructed the first permanent structure: an outhouse(!). My first trip of the year, though, concerned a much more impressive construction. In still-bitter February, I set out to take part in a drone-based 3D scan of Pecos Pueblo.

The ruins of Pecos Pueblo not long after Lieutenant Abert’s curious account

Any early description of the Pueblo was penned by a Lt. Abert in September of 1846. He described how…

The village of Pecos is famed for the residence of a singular race of Indians, about whom many curious legends are told. In their temples they are said to keep an immense serpent, to which they sacrificed human victims. Others say that they worshipped a perpetual fire, that they believe to have been kindled by Monteczuma.

Climbers camouflaged across sheer rock faces; slithering things of regular size hidden directly beneath our feet. Yet signs of civilization remain across the high desert of the mountain west and the plains that undulate and then crack to meet it. Soon, we too will have shelter.

But how? Roadbuilding was but a temporary success, and soon the land will reclaim our efforts. Same for the privy. Perhaps it’s better not to consider such transience, or, better, to embrace it. For the desert is dry, and trash that I wish had disintegrated long ago still blows across the mini mesa, strewn from abandoned habitation miles away. Let us not make the same mistake, when we do build. Let us vanish as we come.

-2019-

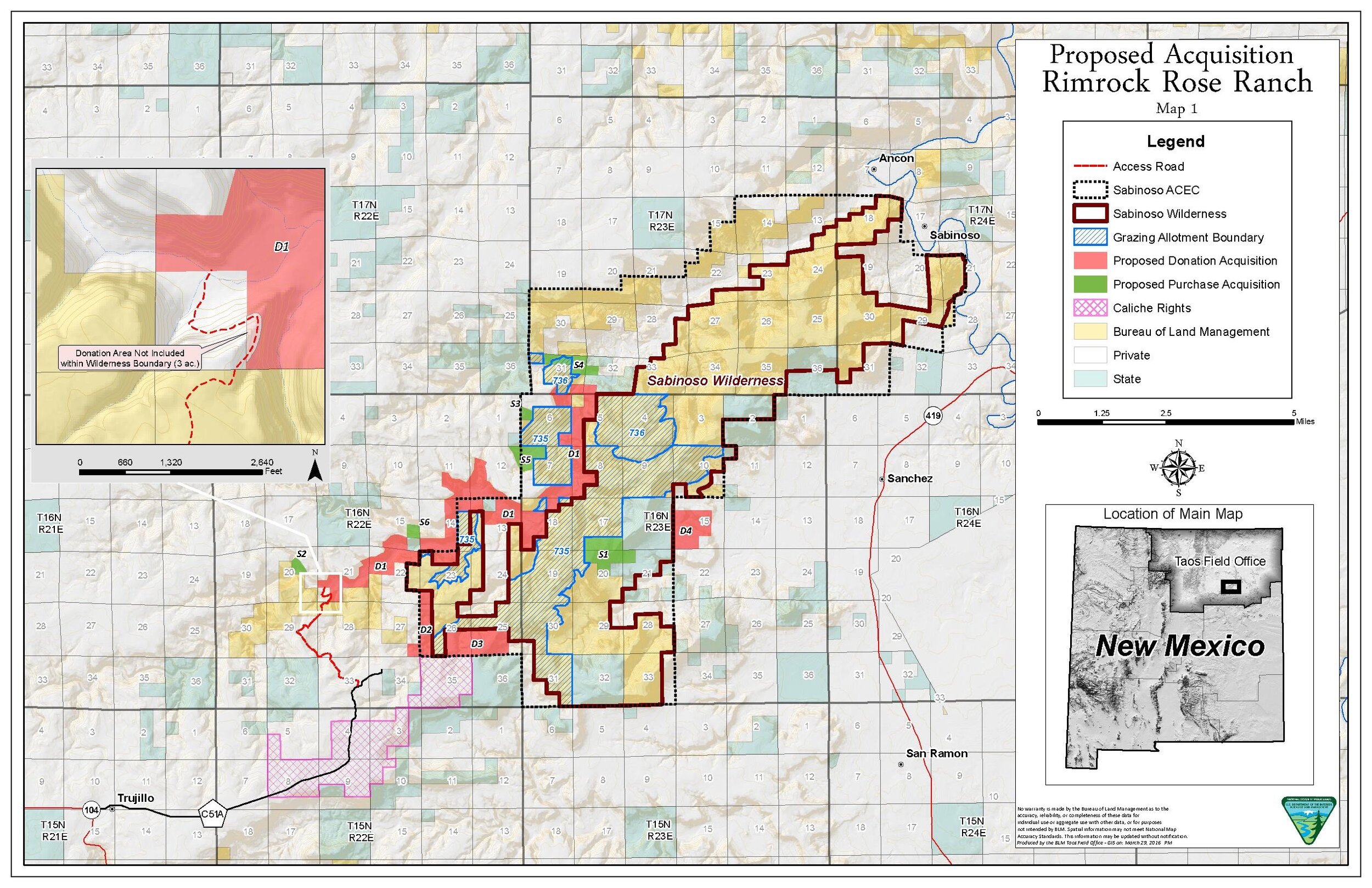

In 2017, nearly 30,000 acres of public land became accessible through the opening of public road access a mere 30 miles Northwest of the property. Seen from the trailhead off county road C51A, the Sabinoso Wilderness is a veritable canyon, comprising branching paths between mesas rising 5000 feet above sea level, coalescing above Trujillo into flat grazing that sprawls until the base of the Sangres at Las Vegas, NM, some 30 miles further West. It’s the edge of the plains, Sabinoso.

Even with the easement, this land remains unapproachable. There are no amenities besides flattened dirt at the trail-head, which is itself hidden miles from a paved road, and few casual day hikers are comfortable opening and closing livestock fences, driving through streams and over sand , and leaving their vehicles atop a mesa while they venture down on foot, another thousand feet down. One has to have a reason to venture this far. Most likely, you will not see another vehicle or another soul at Sabinoso.

We ditched the truck at the trailhead amidst pine and juniper and headed down the mesa, reaching the streambed and cholla patches in half an hour with our light packs. Then through the canyon, flat and 50 yards across, from one sheer sandstone wall to another. Peeking behind boulders and beneath outcroppings, we moved slowly, covering three or four miles in an hour before spotting a spine, which we would attempt to climb. My partner made short work of it. In denim and snake boots, I struggled. Beyond the spine was another canyon - a glimpse into denser wilderness. A future adventure…

-2020-2024-

New Job, now house, new baby. COVID. Missed a year, which I hope will never happen again. Fortunately, we were back in ‘21, and every year since, despite the vast distances that separate the New England coast from the desert Southwest. We explore the nearby towns and cities, paying special attention to the vintage vehicles. A decade approaches.

-2025-

This year marks 10 years since development on “the property”/”Porcupine Ranch”/”mini mesa began in earnest. Of course I mean development in the broadest sense; more of the self-improvement than commercial variety, as evidenced by the scale and nature of actual structures on the land: A travel trailer and an outhouse. The truth is that the landscape itself - and time spent within it - make further development superfluous. Out there, the more you build, the less raw land you have, so development equals failure.

But one still needs a “clean, well-lighted place” - a base of operations from which to launch expeditions, deeper into the evergreen fringes of alpine growth that rim the mesa edges, or down into the ravines that frame an ancient seabed, each filled with their own dangers (bodily harm, far from medicine or law enforcement; spiny, sharp, clawed, fanged adversaries). But the high-desert wilderness and its staggering, desolate beauty is merely a storybook mantra for an office worker with limited PTO.

And so, a decade into this project, we’ve placed a humble cabin, complete with the vital sub-systems to sustain life in the desert southwest, while we plot and plan and otherwise dream of adventures that begin on the doorstep and extend to the dragonoid clouds that twist towards the south, mid-summer, threatening the same rains and floods that would have kept us away for days and weeks in years past.

No rental vehicle is worth the inevitable damage wrought by mesquite and cholla and all manner of thorny shrub spring up between visits, and the two-track roadway now resembles a cow-path, 8 years since its construction. That leaves powersports. ATV, ATC, Dirt Bike, Side-by-Side, Quad Bike; culturo-mechanical mobility devices united by their utility. Two and four stroke engines bolted onto steel frames, open to the elements, but maneuverable (and forgiving) in a way that highway vehicles are not. Enter the now defunct dual-sport known in Asia as the “Serow”, the miniature deer of woodland Japan.

On two, suspended wheels sporting a knobby tires and achieving triple digit MPG with minimal maintenance required on the (“bullet proof”) Yamaha engine, the range and scope of our vision has multiplied considerably. Add to that the water collection, solar array, insulation, wood stove, and emergency radio, and you have a base camp that can sleep 4+ adult humans indefinitely, or at least until things blow over. You can read, strum, shoot, or walk, in any direction, for many miles, until a particularly hearty cow fence outweighs your backcountry fatigue and you stumble home to sip whiskey.

Where does that leave us, 10 years on? Think bigger: To host - family and friends ,of course, but also musicians, writers, and dirt bike racers. To uncover forgotten cemeteries, infiltrate cults, calm the local ghost population wandering from the time of Cortez and beyond, and study the sky for traces of the future. With our headquarters (and four stroke transportation) in place, anything goes. But first, the past. The recent past. Specifically, a 4208 mile road trip, fully loaded, from Melrose, MA, to Newkirk, NM.

Dramatic terrain as far as Ohio, all through Western New England, right across southern Pennsylvania, crossing briefly through West Virginia. Hills that are nearly mountains, lots of timber, intermittent rain. Hit a blown out truck tire on day 2. Then, green. Like a miniaturized jungle set a couple feet off the ground. Yucca, sunflower, mesquite, pinion pine, and those are only the ones I recognize. There are hundreds of species here when it’s wet, plants and animals, and the pasture looks like the Midwest, but spikier.

A millipede dragon crossed the sky, threading the valley from 104 to the lake. Its spiky scales shot out laterally, while legs dangled in the form of rainfall tendrils from a dark belly line, water barely visible by the time it hit ground, but hit the ground it did, and flood it, making travel impossible along the dirt county road . The creature writhed in the sky above, not more than 1000 feet up was its serpentine torso, stretching southwest, towards a distant thunderstorm, which I knew was headed my way.

Stop searching. Face the earth where you can. Literally speaking, it’s all you have to go on.

- Richard Ford